In a cheered action by the state’s environmentalists, the California Coast Commission voted to fine the Texas-based oil company $18 million for failing to obtain the necessary permits and reviews for oil production off the coast of Gabiota coast.

Hours after public comments on Thursday, the committee discovered that Sable Offshore Corp. had for several months by repairing and upgrading an oil pipeline near Santa Barbara without committee approval.

In addition to the $18 million fine, the commissioner ordered the company to halt all pipeline development and recover the land that suffered environmental damage.

“Coastal law is law, and law… was established by the vote of the people,” Commissioner Megan Harmon said. “Sable’s refusal in a very realistic sense is the subversion of the will of the Californians.”

The decision shows a significant escalation in the showdown between coastal and Sable authorities, which the Commission claims has stepped over its powers. This action also occurs when the Trump administration is in stark contrast to the California administration.

It has already received approval from Santa Barbara County for the required work, and its committee approval sables that pipeline infrastructure was only needed if it was first proposed decades ago.

It was not immediately clear how the Houston-based company would respond to the committee’s actions.

“Sable is considering all options regarding compliance with these orders,” read a statement prepared by Steve Rush, Sable’s vice president of environmental and government affairs. “We respect the right to oppose the committee’s decision and seek independent clarification.”

Ultimately, the matter could end up in court. In February, Sable sued the Coastal Commission, claiming that he had no authority to oversee the work.

On Thursday, Rush called the committee’s request part of the “arbitrary permission process,” saying the company had been working with Coastal Commission staff for several months to address concerns. Still, Rusch said his company is “dedicated to reopening project operations in a safe and efficient way.”

The commissioner voted unanimously and voted to issue a suspension order. This is an order that Sable will halt work until approval of the committee and restore damaged land. However, the committee voted between 9 and 2 in favor of the fine.

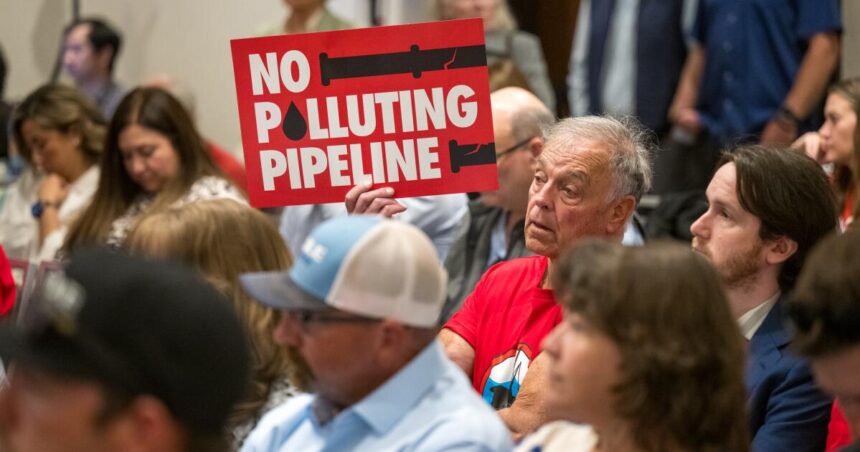

The hearing brought hundreds of people, including scores of Sable employees, supporters and environmental activists. Many wear t-shirts that don’t enable sable.

“We’re at an important intersection,” said Maureen Ellenberger, chairman of the Sierra Club’s Santa Barbara and Ventura branches. “In the 1970s, Californians fought to protect our coastal areas. Fifty years later, we are still fighting. California coasts should not be sold.”

At one point, a stream of 20 Santa Barbara Middle School students testified in a row, with several barely reaching the microphone. “None of us should be here right now. We should all be in school, but we are here because we care,” said Ethan Madei, 14, a ninth grader, who helped organize a trip to a committee hearing of classmates.

Santa Barbara has long been an environmentally friendly community as it is part of the region’s history. The largest spill released an estimated 3 million gallons of oil, prompting multiple environmental laws.

Sable wants to revitalize the so-called Santai Nez Unit, a collection of three offshore oil platforms in federal waters. The Hondo, Harmony and Heritage platforms are all connected to the Las Flores Pipeline system and associated processing facilities.

It was the oil line network that suffered a massive spill in 2015, when the Santay Nes Unit was owned by another company. The spill came when a corroded pipeline burst and released an estimated 140,000 gallons of crude oil near Refugio State Beach. The current work in Sable is intended to repair and upgrade these rows.

At Thursday’s hearing, Sable Supporters argued that the upgrade would make the pipeline network more reliable than ever.

Mai Lindsey, a contractor working on Sable’s leak detection system, said he “unfairly” found how the committee was claiming itself in their work.

“Are you in your lane to force this?” asked Lindsay.

She said people need to understand that focusing on previous spills is no longer relevant given how dramatically the technology in her industry has changed: “We learn and improve,” she said.

Steve Bulkcom, a Sable contractor who lives in Orange County, said he has been working on the pipeline for 40 years and this is sure to be the safest. He repeatedly controversed over his “not my backyard” attitude.

“We know that the pipeline could be safe,” Balkcom said.

Sable claims that corrosion repair work can proceed based on the original permit of the pipeline from the 1980s. The company argues that such permissions are still relevant as its work only repairs and maintains existing pipelines that do not have new infrastructure in place.

The Coastal Commission rejected the idea Thursday. We show some photos of Sable’s ongoing pipeline work, committee executive director Lisa Haage.

Commission staff also argue that the current work is far from the original permit, requiring new standards to address the corrosive trends of the pipeline.

“They not only worked in sensitive habitats, they refused to comply with orders issued to address those issues without adequate environmental protection and in times when sensitive species were at risk,” Haage said at the hearing.

However, Sable said the project “meets harsher environmental and safety requirements than any other pipeline in the state.”

The company estimates that if the Santa Ynez unit is fully online, it will produce an estimated 28,000 barrels of oil per day, while generating $5 million per year in new county taxes and another 300 jobs. Sable will resume offshore oil production in the second quarter of this year, but the company has admitted that there are some regulatory and surveillance hurdles remaining.

Most notably, the reboot plan must continue to be approved despite several other parts being reviewed, such as state parks and the state water resource management board.

The commissioner on Thursday was grateful for the community’s input from Sable employees, who Harmon called “harmon the hardworking people.”

“Coastal development allows jobs to be safe,” Harmon said. “They make our work safer, not just our environment… They make our work safer for the people who work.”

She urged Sable to work in cooperation with the committee.

“We can do a good paying job, we can protect and protect the coast,” Harmon said.

However, some environmentalists said Thursday’s findings should further raise questions about Sable’s larger projects.

“How can we trust that this company operates responsibly, safely or in compliance with regulations and laws?” said Alex Katz, executive director of the Santa Barbara-based Center for Environmental Defense, in a statement. “California cannot afford another disaster on our coast.”